I recently read that practicing gratitude leads to better health, more happiness, and stronger relationships. In thinking about what I’m grateful for this Thanksgiving holiday, I found that “hearing loss” rises somewhere near the top of my list.

Thankful for My Hearing Loss?

When I say “I am grateful for my hearing loss,” I hope it doesn’t seem like a disingenuous attempt at pandering. Hearing loss is part of my identity. When I reflect on my life with hearing loss, and realize just how much it influenced my perspective and my passions, I feel genuinely thankful.

I work every day as a design expert, a technology enthusiast, and a tireless advocate for accessibility. I attribute my lifelong interest in these areas directly to my own experience with hearing loss. Over time, my interests and education developed into true passions (near obsession, perhaps!). These passions now guide my personal mission. Hearing loss made me an ambassador for simplicity and social good.

A “Visual Listener”

Before receiving my first hearing aids at age 6, I taught myself to “listen visually.” I read lips, watched facial expressions, and took notice of body language. This “visual training” made me an attentive listener and careful observer, which in turn led to empathy and compassion. And perhaps that gives me an advantage in connecting with others that may not come so easily to my friends with “perfect hearing.” I like to think I’ve become amiable, diplomatic, and open-minded—and I owe that, in part, to hearing less well than others.

An Eye for Design … and Usability

“Visual” is (still) my primary communication channel. So, I am naturally drawn to design and usability. Of course, my particular interest includes the design and usability of hearing aids and hearing accessories.

My early hearing aids were clunky and obtrusive. Thick black eyeglasses with hearing aids built into the frame weren’t exactly cool or empowering. They seemed to instantly and loudly signal my “special needs,” a differentness that too easily brought pity and too often resulted in marginalization.

Surely, I thought, we can do better than this! My curiosity and my quest for better design eventually led me to the Pratt Institute in New York, where I studied Design Management. And I’m honored to have been a protégé of Sam Farber, founder of OXO, the creator of Good Grip Kitchen products. Without hearing loss, I might not have discovered my drive for good design.

An Imagination Fascinated With Technology

Because my hearing aids were obvious, I learned to turn awkward stares into light-hearted humor. I often pretended that my space-age apparatus could receive shortwave radio communications. Ball games, weather reports, the latest news. I imagined it all built into my personal device. And this long before the digital innovations that made such dreams an everyday reality.

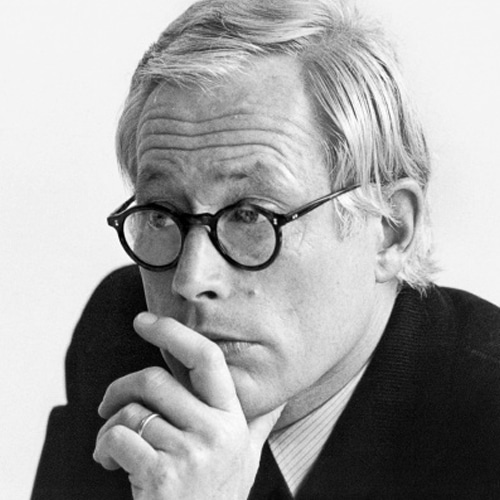

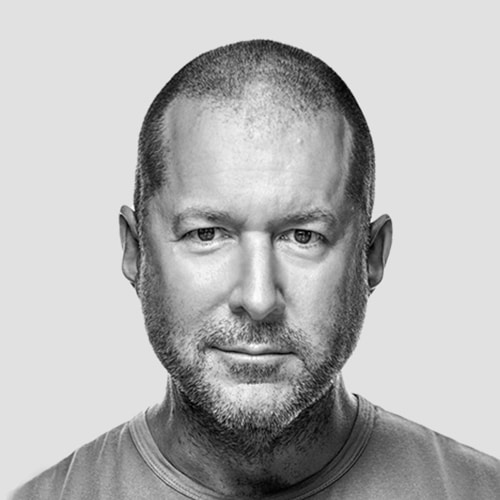

Imagining advances in technology is the stuff of science fiction and, as it turns out, science fact. Enter Dieter Rams, an industrial designer for Braun, one of my heroes. His philosophy suggests that good design must be innovative, useful, understandable, unobtrusive, honest, durable, consequential, environmentally-friendly, and minimal. For a kid who wears hearing aids, this was music to my ears! Dieter’s philosophy inspired the iPod designs of Jony Ive, designs which influenced the development of the iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and so on.

Well, no wonder I ended up at Apple.

An Advocate for Accessibility

Working at Apple, I quickly realized that all products with good design and genuine usability, especially tech products, rely on the principles of accessibility. My appreciation of their award-winning design and my enthusiasm for accessibility created my opportunity to serve as Accessibility Advocate for Apple, Inc. Once again, thank you hearing loss.

Whenever I speak or teach about accessibility, I encourage my audience to think of it as “accessing abilities”. We avoid the word “disability” at all costs. Why? Because the “dis” in “disability” suggests something broken, apart, a “negative, reversing force.” But we’re not broken, we’re just human. Since no one has perfect abilities, we all need greater accessibility for some part of our life. And creating a world full of accessible things, places, and services, benefits everyone.

Everyone.

Accessibility for All

For example, Ray Kurzweil, a brilliant inventor and futurist educated at MIT, casually conversed with a fellow airline passenger who happened to be blind. It inspired him to invent a “reading machine” that could identify written text and read it aloud (later acquired by Xerox). His design for reading accessibility led to a friendship with Stevie Wonder. Wonder challenged Kurzweil to help him create better electronic music. So, Kurzweil developed a realistic “music sampling” algorithms so powerful and effective, it earned him a Grammy Award. Moving from text-to-speech to speech-to-text, Kurzweil became a pioneer in voice recognition software. Now, he works at Alphabet, Inc. with a singular focus: “to bring natural language understanding to Google.”

So, if you enjoy modern music (acoustic or electronic—can you tell which is which?), if you rely on scans and photos to capture text, or if you dictate instructions, searches, or texts to your device, you are the beneficiary of design and technology focused on accessibility.

Hey, Google. Please tell Ray Kurzweil thanks.

My Hearing Loss and My Future

My hearing loss influenced my creativity, made me a technophile, and taught me about accessibility. It also fills me with greater compassion. Practicing accessibility principles in physical and digital spaces opens the horizon to other possibilities. Not only does it show kindness and compassion for others, but the good we do ripples out into the world in amazing, often unexpected ways. It seems we cannot help someone without, in some way, helping everyone. I guess that’s another thing I learned from life with hearing loss. And for that, I’m truly grateful.